An annual activity of the University’s MLK Initiative: “Let Freedom Ring!” is to take one of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s signature speeches and use it as a curricular launching pad for deeper reflection about the enduring legacy of Dr. King and what his movement building for economic and racial justice means for living out our Georgetown mission today. Mission in Motion reflected on last year’s efforts that included speeches from both MLK and Congressman John Lewis (D-Ga.), timely selections for locating hope amidst the desolations of social injustice, particularly manifested in the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

This year’s speech, the famous “I Have a Dream” address in 1963, is a fitting choice for 2022. Georgetown’s Center for Social Justice Research, Teaching & Service (CSJ), one of the co-sponsors of the initiative, commented that this “choice might seem cliché or obvious.” But the inspiration for choosing it arises in part from an article by Dr. Ibram Kendi, who lamented the myriad ways that Dr. King’s dream speech has been distorted by intentional efforts to convert the landmark speech into advocacy for “color-blind civil rights.” Rather, Dr. King’s speech is actually a challenging and demanding call, issued then but still reverberating today, to work for justice in a multiracial democracy by directly addressing the roots and effects of structural racism.

In his own lifetime, Dr. King would address some of these distorted impressions caused by a single line in the speech that he dreamed “that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” He remarked in 1965 that “one day all of God’s Black children will be respected like his white children” and in 1967 that the “dream that I had [in 1963] has at many points turned into a nightmare.”

As the United States continues to experience social, cultural, and political polarization around persisting racial injustices in all facets of society, MLK’s iconic 1963 speech presents a valuable opportunity to renew the discussion in 2022 and re-commit to tangible actions at Georgetown. For SCS students, staff, and faculty, integrating the “I Have a Dream” speech into classes and co-curricular spaces can spur critical reflection and action about racial inequities in the various professional industries that are the subject of SCS academic programs. For faculty and staff interested in Teaching the Speech in their classrooms and educational spaces this year, please fill out this form to learn more about the pedagogical resources to support this work.

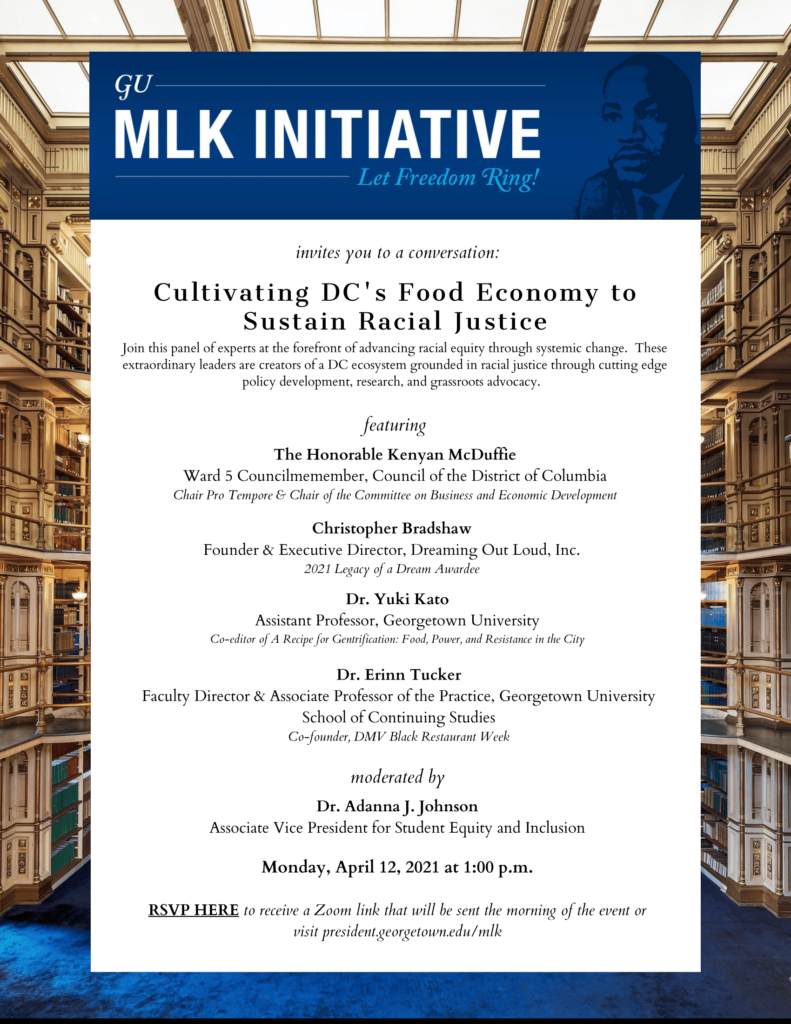

If you want to more deeply explore Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, you should also attend next week’s annual Teach-In event over Zoom on Tuesday, January 11 from 11:30 a.m. to 1:45 p.m. ET (RSVP). The Teach-In will feature:

- 11:30 a.m.: Community Gathering with Music

- 12:00 p.m.: Welcome by Ryann Craig, Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs followed by a student reflection by Veronica Williams (C’23) and mini-keynotes by Virginia State Senator Jennifer McClellan and Neonu Jewell (L’04) of the African American Policy Forum

- 1:00 p.m.: Dialogue with our three speakers facilitated by Ijeoma Njaka (G’19), Senior Program Associate for Equity-Centered Design at the Red House

- 1:40 p.m.: Gratitude by Maya Williams, Office of Student Equity and Inclusion

Faithfully celebrating the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. means more than taking a day off from work. To witness to Dr. King’s legacy is to make a commitment to carry on his movement efforts for social justice and the common good. I hope you are able to attend the January 11 Teach-In and find ways to reflect and act at Georgetown on the enduring lessons of “I Have a Dream.”